Release Date: September 12, 2025 (USA)

Runtime: 108 minutes (1h 48min)

Rated: R for strong bloody violence, grisly images, suicide, pervasive language, sexual references

Production Companies: Vertigo Entertainment

Producers: Roy Lee, Steven Schneider, Francis Lawrence, Cameron MacConomy

Cinematography: Jo Willems

Editing: Mark Yoshikawa

Music / Composer: Jeremiah Fraites

The Long Walk (2025)

Writer(s): JT Mollner (screenplay), based on Stephen King’s novel (Richard Bachman)

Starring: Cooper Hoffman, David Jonsson, Garrett Wareing, Tut Nyuot, Charlie Plummer, Ben Wang, Roman Griffin Davis, Josh Hamilton, Judy Greer, Mark Hamill

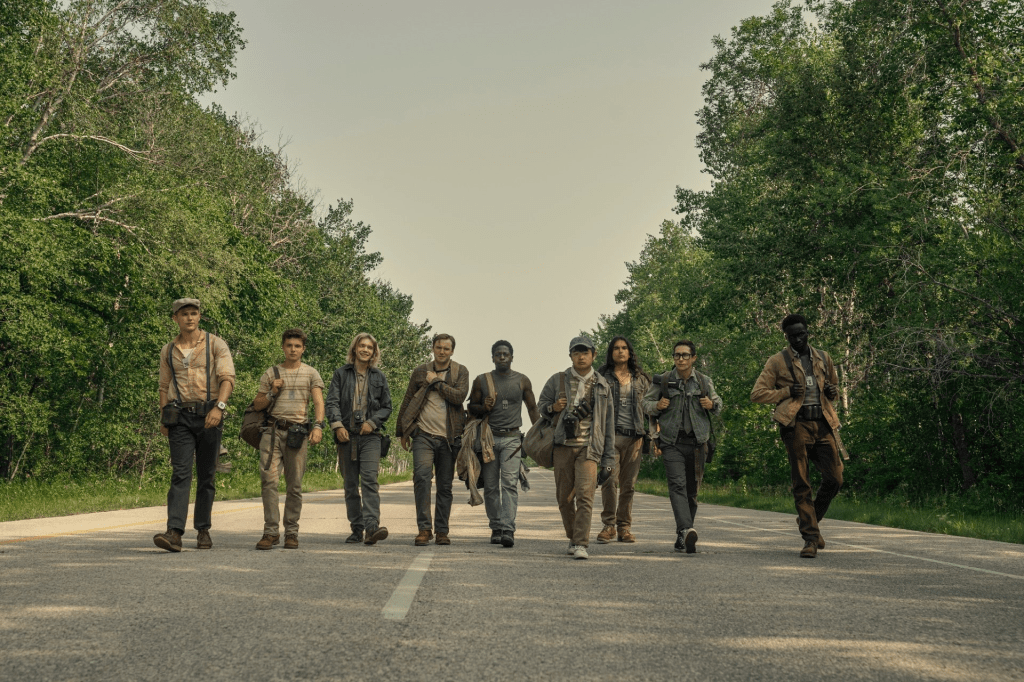

From the very start, the film refuses to shy away from its brutality. The first display of violence is presented in what The Major (Mark Hamill) calls its “full glory.” This desensitization is not only one of the core messages of the story but also a reflection of both the time period in which the film is set and the world we live in today. The Long Walk feels tailor-made for Francis Lawrence, a director whose eye thrives in the shadows of dystopian futures.

At the heart of the film are Cooper Hoffman as Ray Garraty and David Jonsson as Peter McVries, who serve less as lead and sidekick than as co-leads. While certain moments in the script may falter in dialogue or pacing, the strength of their performances more than compensates. Hoffman and Jonsson carve out a bond that becomes the film’s soul—a brotherhood forged under impossible circumstances. If anything, their shared history could have been fleshed out further, but the journey they endure together is carried powerfully by their commitment.

The success of the film hinges largely on their shoulders, and had the performances been lesser, the result could have easily unraveled. Fortunately, both actors embody their roles so completely that the adaptation’s deviations from the book feel purposeful. The cinematography heightens this immersion: sweeping shots capture the boys’ endless march across streets, towns, and states, contrasting early-morning light and dusky skies with the sinister reality lurking beneath the spectacle. For all its visual beauty, the Long Walk itself is a cruel reminder of totalitarian control and the fragility of human hope.

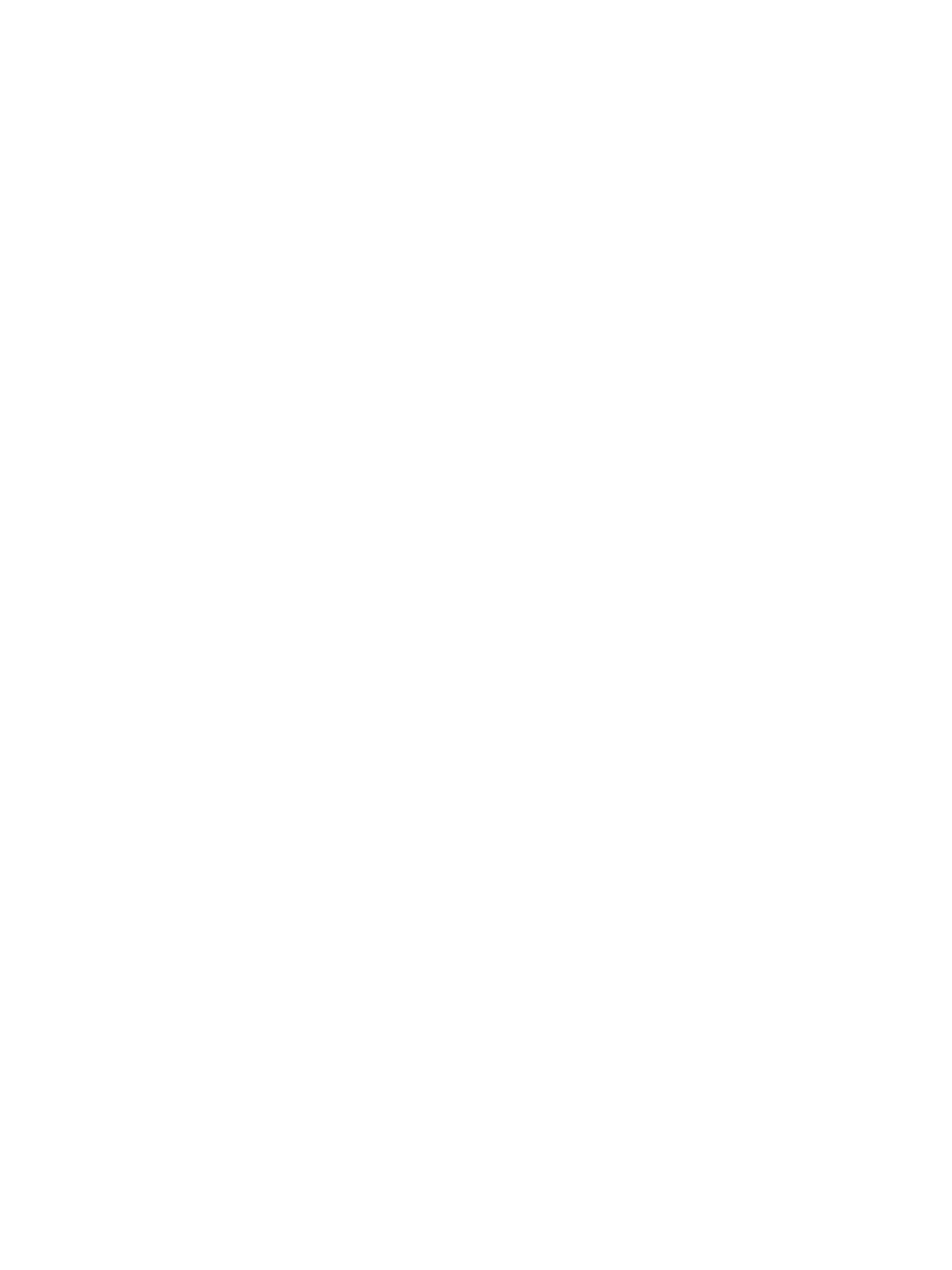

Ray joins the walk against his mother’s wishes, haunted by guilt and desperate to silence an inner voice—a motivation distinct from the novel. Alongside him, we meet other participants: Hank Olson (Ben Wang), Arthur Baker (Tut Nyuot), Gary Barkovitch (Charlie Plummer), Billy Stebbins (Garret Wareing), Collie Parker (Joshua Odjick), and more. Each carries his own reason for entering, but in a post-war America riddled with despair, the Walk offers one of the few perceived escapes. Yet the rules are merciless: win the Walk or die.

The contest tests not just physical endurance but psychological resilience, all while being broadcast to the nation like a warped sporting event. Echoes of the Vietnam War reverberate here, with violence turned into mass spectacle—both scrutinized and glorified. This duality reinforces the film’s critique of desensitization and the cultural hunger for suffering packaged as entertainment.

Beyond its social commentary, the film builds a sense of community. As viewers, we walk alongside the boys, sharing in their fatigue, their fleeting joys, and the fragile connections forged under duress. The story reminds us that while adversity creates resilience, it is the relationships born from hardship that linger longest. Though set in an alternate dystopia, the themes remain strikingly relevant—not only to the era in which Stephen King’s novel was written but also to our present political climate.

The dystopia extends beyond the Walk itself. Lawrence weaves in the suffocating presence of censorship—banned books, silenced music, and erased media—which becomes increasingly central as the plot unfolds. The restriction of art and thought deepens the characters’ hopelessness and mirrors today’s cultural battles.

Of course, dystopian cinema is nothing new. The genre often mirrors the anxieties of the time in which a film is released. The Long Walk embraces this tradition openly, wearing its themes on its sleeve. At times, its approach is overt, but Lawrence executes it with care, grounding the spectacle in human emotion. Dialogue leans into the expected formula of dystopian storytelling—grand ideas colliding with intimate human truths—but its delivery is heartfelt enough to resonate.

What distinguishes the film is its balance of politics and humanity. It wrestles with questions of power, class, and control, yet never abandons heart, empathy, or the fragile bonds that sustain people under pressure. Still, it forces us to confront the darker flipside: how quickly compassion can curdle into vengeance when survival is at stake. That tension—between hope and cruelty, solidarity and self-preservation—is what gives The Long Walk its bite.