Release Date: July 18, 2025 (U.S.)

Runtime: 2 h 28 m (148 min)

Rating: R

Production Companies: A24, IPR.VC, 828 Productions, Square Peg

Producers: Ari Aster, Lars Knudsen (+ exec. producers Alejandro De Leon, Robert Dean, Harrison Huffman, Todd Lundbohm, Andrea Scarso)

Cinematography: Darius Khondji

Music / Composers: Bobby Krlic (aka The Haxan Cloak) and Daniel Pemberton

Eddington (2025)

Director & Screenwriter: Ari Aster

Starring: Joaquin Phoenix, Pedro Pascal, Emma Stone, Austin Butler, Luke Grimes, Deirdre O’Connell, Micheal Ward, Clifton Collins Jr., William Belleau

As I watched Eddington for a second time, I could feel the divisiveness around its narrative growing—and experienced it first-hand when a couple walked out of the theater mid-film. Unsurprisingly, it was during one of the most charged sequences involving the George Floyd storyline and the Black Lives Matter protests. But the more I thought about it, the more I realized: a film like this was inevitable. Everything depicted in Eddington happened. I know that because I lived through it—not long ago, but what now feels like an entire lifetime away. I’m just glad that Ari Aster was the one to get a head start on this new wave of pandemic-era social satires.

That’s not to say Eddington is the first film to explore the COVID pandemic. Others have tried. But none with this level of sprawl, black comedy, visual ambition, or unflinching discomfort. Aster calls it a “modern western,” which at first felt like a reach—until I rewatched it. The Western elements are there: the desert town, the antihero sheriff, the tension of order vs. chaos. But it’s the modernity—the masks, the protests, the livestreams, the data center, the fringe conspiracies—that root this film squarely in 2020 and beyond. It’s a haunting time capsule.

When I say the film was inevitable, I mean that it was only a matter of time before someone made a film this hyper-politicized, this stuffed with cultural commentary. It’s a satire, yes—but one that grows more potent the more you compare it to real life. Eddington doesn’t fictionalize reality; it magnifies it, mutates it, pushes it just enough to provoke discomfort while still feeling eerily plausible.

The pandemic didn’t just bring fear of illness. It ignited every pressure point in American society. It exposed our addiction to screens and our widening political rifts. It showed us, again, the brutal cost of systemic racism—none more vividly than in the murder of George Floyd. That video went viral not just because it was horrifying, but because we were all home, trapped inside, glued to screens. Our phones became windows into a world on fire. And what followed was one of the largest civil rights movements in history.

Aster, to his credit, doesn’t claim authority over these events. He critiques them from his own vantage point. He doesn’t speak for the Black community, but he observes the behavior of those around him. In a world where some were fighting for justice and others were co-opting activism for clout or political gain, Eddington aims its sharpest satire at the latter.

So we enter this strange, insular New Mexico town, where information arrives late and change is slower still. The central figure is Sheriff Joe Cross (Joaquin Phoenix), a textbook conservative whose mayoral campaign is born out of anti-mask rhetoric. The film initially centers on his wife Louise (Emma Stone), but quickly shifts as Joe’s spiraling ambitions take over. His worldview begins to crack when he’s confronted by Officer Butterfly Jimenez (William Belleau) from the neighboring San Pueblo department. Their first interaction—centered on the simple act of mask-wearing—sparks the film’s broader chaos. From there, Eddington unleashes a kaleidoscope of intersecting stories, many told through screens, that paint a darkly comic portrait of American dysfunction.

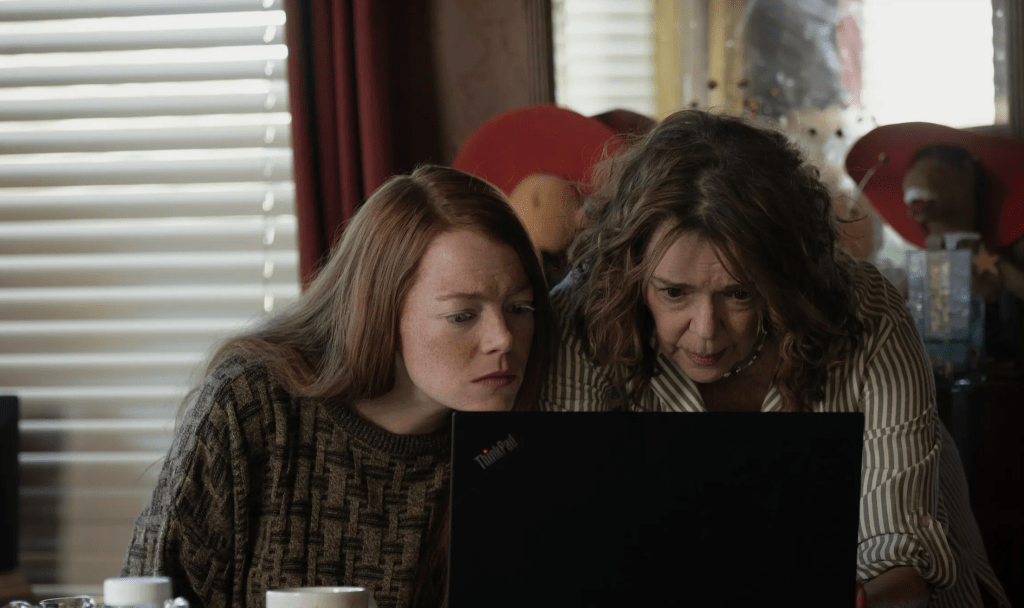

One of the most powerful threads in the film is Louise’s unraveling. She begins the film deeply uncomfortable with physical touch, an early sign that something isn’t right. Living under lockdown with her conspiracy-minded mother Dawn (Deirdre O’Connell) only accelerates her mental decline. When Joe announces his mayoral campaign, Louise and Dawn spiral into the orbit of Vernon Jefferson Peak (Austin Butler), a cult-like guru whose charm masks a darker past. His stories hint at sex trafficking and systemic abuse, while Louise’s reactions suggest a buried trauma of her own. Aster doesn’t over-explain. He lets the discomfort simmer, making the subtext feel all the more suffocating.

We then meet Mayor Ted Garcia (Pedro Pascal) and his son Eric (Matt Gomez Hidaka), whose relationship to Joe is fraught with tension. The pandemic, particularly the mask mandate, acts as a flashpoint that reignites old political feuds. Eric, meanwhile, becomes entangled in the performative activism of the moment—more interested in “getting the girl” than any actual social change. His friend Brian (Cameron Mann), a white teenager trying to navigate new rules of social and racial politics, begins the film innocent enough. But by the end, he’s gone full far-right, shaped by online influencers and trauma.

Much of the film’s brilliance lies in how it charts these pipelines: how young people slip into extremism, how adults cling to authority, how political theater becomes a stand-in for real action. And then there’s Solid Gold Maga Karp—the looming data center that functions as both symbol and antagonist. Pushed by Ted Garcia’s campaign, the center’s presence warps everything around it. It’s the nucleus of conspiracy, the carrot for corrupt politicians, and a tech-age fortress of surveillance. It’s not just a place. It’s an idea, a threat, a cult of its own.

The ANTIFA-like figures that arrive toward the film’s end throw the town into chaos, and their ambiguous role blurs the lines between protest and provocation. Are they real activists, or part of a deeper conspiracy? It’s unclear—and intentionally so. In a world this chaotic, truth becomes negotiable. Violence becomes background noise. Assassinations feel like glitches in a system already corrupted beyond repair.

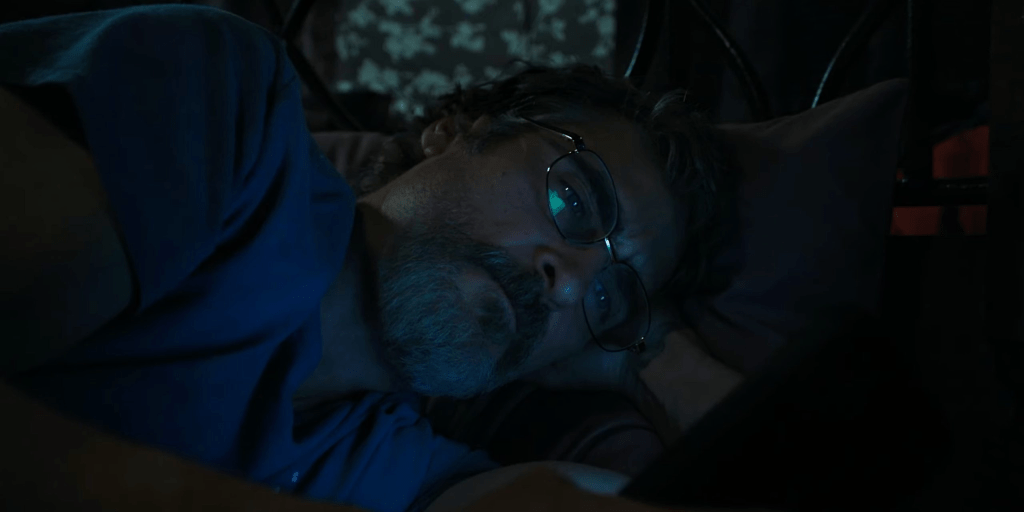

Eddington understands that screens shape perception. One of the film’s best moments involves Joe secretly recording a confrontation with Ted Garcia by placing a phone in his shirt pocket. Screens—phones, tablets, laptops—are ever-present. They frame characters’ lives and also the film itself. Aster plays with aspect ratios, embedded media, and news-style footage to remind us: this is a movie about watching. About how we experience catastrophe through a digital filter. The same filter that warped our reality in 2020.

It’s a bold film, and an unflinching one. And yes—it’s controversial. Many critics have accused Aster of exploiting the Black Lives Matter movement or trivializing George Floyd’s death. But to me, Eddington doesn’t take sides. It takes aim. It shows the absurdity of white people trying to co-opt struggles they don’t understand, and it mocks both liberal virtue-signaling and conservative fearmongering. Most importantly, it holds Sheriff Joe Cross accountable as a symbol of performative conservatism. His descent into political madness feels less like a stretch and more like a reflection of people we’ve all seen—or voted for.

By the film’s end, Joe becomes mayor, but only after being manipulated by Dawn and enabled by Brian, whose conversion to right-wing ideology feels depressingly plausible. The film ends in a state of unease: with Joe essentially incapacitated, Louise broken, and a town barely holding itself together. Even the ANTIFA plot remains ambiguous—perhaps by design, because in this film, no one’s hands are clean.

And while we’re on the topic of commentary, the film’s handling of Native American characters—particularly Officer Butterfly Jimenez—is worth discussing. He and his colleagues are shown as competent, principled, and deeply aware of the injustices surrounding them. In contrast, Joe and his department are callous, disrespectful, and ignorant. When Joe desecrates a Native history museum during a chaotic shootout, it’s not subtle. Aster wants you to see who gets trampled in the name of power.

Then there’s the transient—the homeless man who opens the film and reappears throughout, only to be killed by Joe in a bar. He seems to symbolize something greater: someone discarded by society, disconnected from political theater, and perhaps the only character who’s seen it all and opted out. His death is the first moment Joe truly seizes control. And it marks the beginning of his unraveling.

Technically, the film is remarkable. The cinematography is breathtaking. The editing moves like wildfire. The performances are universally excellent. Joaquin Phoenix turns in yet another masterclass as a man you loathe but can’t look away from. Pedro Pascal plays against type with nuance. Emma Stone and Austin Butler deliver haunting performances. And Deirdre O’Connell might be the film’s secret weapon—her paranoid, broken worldview anchoring some of its most disturbing scenes.

The film is long—2 hours and 25 minutes—but it earns every minute. It’s messy, sprawling, and chaotic by design. Just like 2020. And while not everyone will be ready to look back on that year through a satirical lens, I’d argue that Eddington is exactly the kind of reflection we need. Is it too soon? Maybe. But maybe that’s why it matters. Because it forces us to ask: what the hell happened to us—and why are we still pretending it didn’t?

Aster’s not just ahead of the curve. He’s holding up a cracked mirror to a time we all lived through and would rather forget. But in doing so, he reminds us that satire isn’t about distance. It’s about proximity. And Eddington might be closer than we think.