Release Date: Theatrical release — December 24, 2025 nationwide

Runtime: 110 minutes (1h 50m)

Rated: R – for thematic content and language

Production Companies: Saint Laurent Productions, Badjetlag, CG Cinéma, The Apartment Pictures, Fremantle, Les Films du Losange, Weltkino, Cinema Inutile, Fis Éirann/Screen Ireland, Hail Mary Pictures

Producers: Charles Gillibert, Joshua Astrachan, Carter Logan, Atilla Salih Yücer

Cinematography: Frederick Elmes & Yorick Le Saux

Editing: Affonso Gonçalves

Music/Composer: Jim Jarmusch

Father Mother Sister Brother (2025)

Director & Writer: Jim Jarmusch

Starring: Tom Waits, Adam Driver, Mayim Bialik, Charlotte Rampling, Cate Blanchett, Vicky Krieps, Sarah Greene, Indya Moore, Luka Sabbat, Françoise Lebrun

Jim Jarmusch’s Father Mother Sister Brother is titled with such directness that its thematic intention is impossible to misread. Yet, the film itself is anything but blunt. Rather than relying on flashy dialogue or overt emotional signposting, Jarmusch places his emphasis on blocking and choreography, recurring visual motifs, and performances that treat the human body as its own language. Communication here exists in posture, in glances, in proximity — often more so than in words themselves.

The title alone gestures toward immediacy and universality. At the very least, everyone has a mother and a father; whether they remain present is an entirely different matter. Siblings, too, exist in varying forms — present, absent, imagined, or emotionally distant. Across three distinct yet connected vignettes, Jarmusch explores family as a shared human condition rather than a singular experience. He deploys subtle, almost playful repetitions — coordinated clothing, the clink of different drinks, a conspicuously worn Rolex — as connective tissue. While each story clearly stands on its own, separated by geography, characters, and circumstance, they are ultimately bound by a common emotional grammar: the universal language of family.

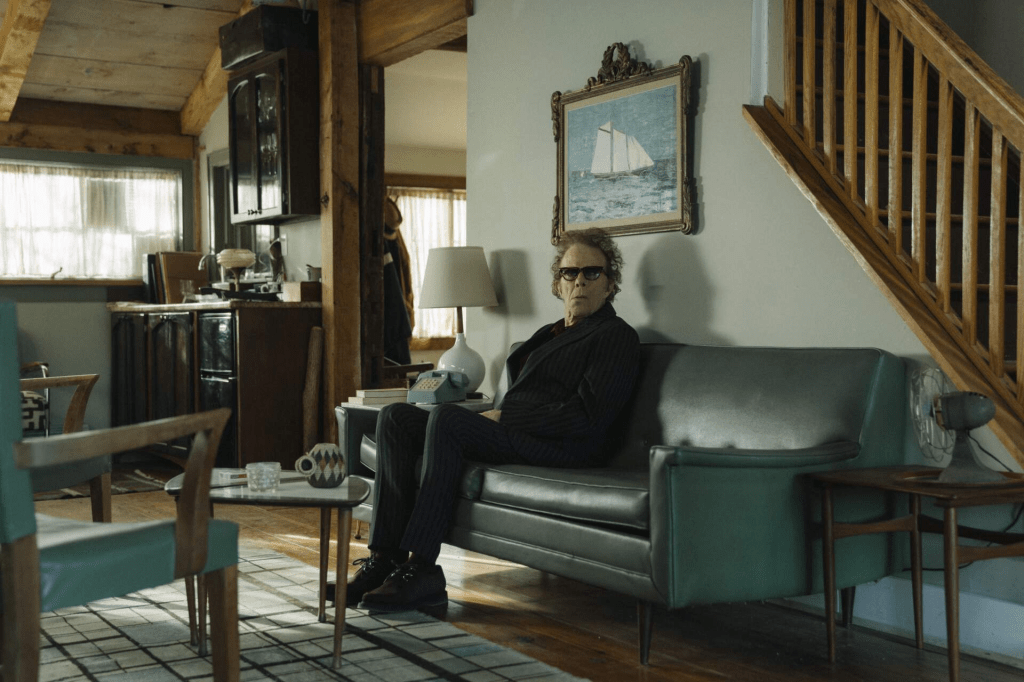

The film opens with siblings Jeff (Adam Driver) and Emily (Mayim Bialik) traveling to visit their reclusive father (Tom Waits). This first chapter establishes the film’s preoccupation with unspoken communication — an undercurrent that persists throughout all three stories. Some interactions may read as awkward or even forced, but that discomfort feels intentional. Jarmusch captures the inherent tension of familial obligation: the idea that connection exists regardless of ease, comfort, or emotional fluency.

What unfolds is less about what is explicitly said and more about what is withheld. There is clearly more history between these three than the film chooses to articulate outright, leaving the audience to read between gestures, silences, and half-formed exchanges. Driver, Bialik, and Waits are tasked with conveying emotional nuance through restraint, resulting in a subtle psychological dance — a quiet game of cat and mouse where guilt, accountability, and deception simmer beneath a veneer of civility. The visit feels necessary, if not entirely wanted, driven by love as much as it is by endurance and emotional survival.

The second vignette shifts focus to a matriarch, Catherine (Charlotte Rampling), and her two daughters: Timothea (Cate Blanchett) and Lilith (Vicky Krieps). Once again, the true narrative resides beneath the surface. Dialogue remains polite, measured, and at times deliberately shallow, while body language and facial expressions quietly betray years of unresolved tension. Rampling, Blanchett, and Krieps deliver performances that feel acutely attuned to generational difference — not just in age, but in worldview, self-presentation, and emotional armor.

As with the first story, there is an undercurrent of deception, or at least selective truth-telling, operating between the characters. Yet it is met with a familiar leniency, justified by the same universal framework of family. Jarmusch mines empathy from this dynamic, allowing the audience to recognize themselves in these interactions — in the roles of eldest and youngest, in the expectations placed upon daughters, and in the compromises made to preserve harmony during moments meant to signify closeness. The tea-time reunion becomes less about reconnection and more about performance, where civility masks deeper fractures. In many ways, this segment functions as a gendered mirror to the first vignette, exchanging parental roles while reinforcing the same themes of obligation, concealment, and emotional inheritance.

The final story brings us to Paris, where twin siblings Skye (Indya Moore) and Billy (Luka Sabbat) reunite following the sudden death of their parents in a plane accident. The absence of the parents here marks a tonal shift. Rather than direct confrontation, we are given fragments — memories, belongings, impressions — allowing the parents to exist only through what they leave behind. Jarmusch moves from depicting family as an active, negotiated relationship to one defined by aftermath and residue.

This vignette underscores how family persists even after its foundational figures are gone. Memory replaces presence, and grief becomes a quieter, more internal process. By situating these stories across different countries, Jarmusch reinforces the notion that familial dynamics transcend culture and geography. While some viewers may find the repetition across segments deliberate to the point of redundancy, the film’s power lies in its passivity. This is not a plot-driven work, nor does it offer exhaustive backstories. Instead, it presents fleeting glimpses — enough to engage, enough to resonate — trusting the audience to fill in the emotional gaps.

Skye and Billy’s story serves as an effective closing chapter, reframing the earlier vignettes in retrospect. The previous encounters illustrate the small, often maddening adversities that arise when parents and children coexist. This final segment reveals what remains once those relationships can no longer evolve — how love, flaws, and unresolved tensions are preserved as memory. It becomes clear that much of what we forgive or sideline in the people we love is sustained precisely because of that love.

Ultimately, what Jarmusch extracts from these three modest tales is a meditation on family as an umbrella term — expansive, unavoidable, and deeply personal. He returns again and again to ideas of deception, compromise, and emotional distance, not as condemnations but as inherent aspects of familial bonds. The cinematography works in quiet tandem with the film’s blocking and choreography, visually reinforcing relationships before dialogue ever needs to articulate them. Meaning emerges through exchanged looks, generational humor, and the physical spacing between bodies within a frame.

Family is universal. Jarmusch understands this, acknowledges it without sentimentality, and constructs a film rooted in shared experience rather than narrative excess. We are given just enough insight into these characters to feel their weight, yet not enough to fully know them — and that restraint feels intentional. Father Mother Sister Brother satisfies while leaving a lingering hunger, much like family itself: familiar, incomplete, and impossible to fully resolve.