Release Date: November 7, 2025 (Limited)

Runtime: 133 minutes (2h 14m)

Rated: R — some language, a sexual reference, and brief nudity

Production Companies: Mer Film, Eye Eye Pictures, MK Productions, BBC Film, Lumen Production, Komplizen Film, Zentropa, Zentropa Sweden, Film i Väst, Alaz Film

Producers: Maria Ekerhovd, Andrea Berentsen Ottmar

Editing: Olivier Bugge Coutté

Music / Composer: Hania Rani

Sentimental Value (2025)

Writer(s): Joachim Trier & Eskil Vogt

Starring: Renate Reinsve, Stellan Skarsgård, Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas, Elle Fanning, Cory Michael Smith, Anders Danielsen Lie

Universally speaking, almost everyone can relate to the complications, ruptures, and unfinished business that come with family — especially when it comes to our parents. The harder task in storytelling isn’t illustrating that friction, but making it feel lived-in: relatable yet specific, raw yet hopeful, messy yet somehow tethered to grace. Joachim Trier achieves all of this in Sentimental Value, a film that quietly but confidently stands among the year’s strongest.

In Trier’s hands, the film becomes a tapestry — layers on layers of narrative, memory, and emotional archaeology. There are stories within stories, pasts bleeding into presents, family history intertwining with current-day fractures, and an evolving sense of what connection can look like when forgiveness is murky and timing never feels right. Even as the film unravels in ways that feel chaotic or imperfect (as real families do), Trier keeps it grounded: emotionally perceptive, visually delicate, empathetic toward every character, and rhythmically shaped by his music choices. It’s everything a piece of filmmaking should aim to encapsulate, executed with his signature softness and clarity.

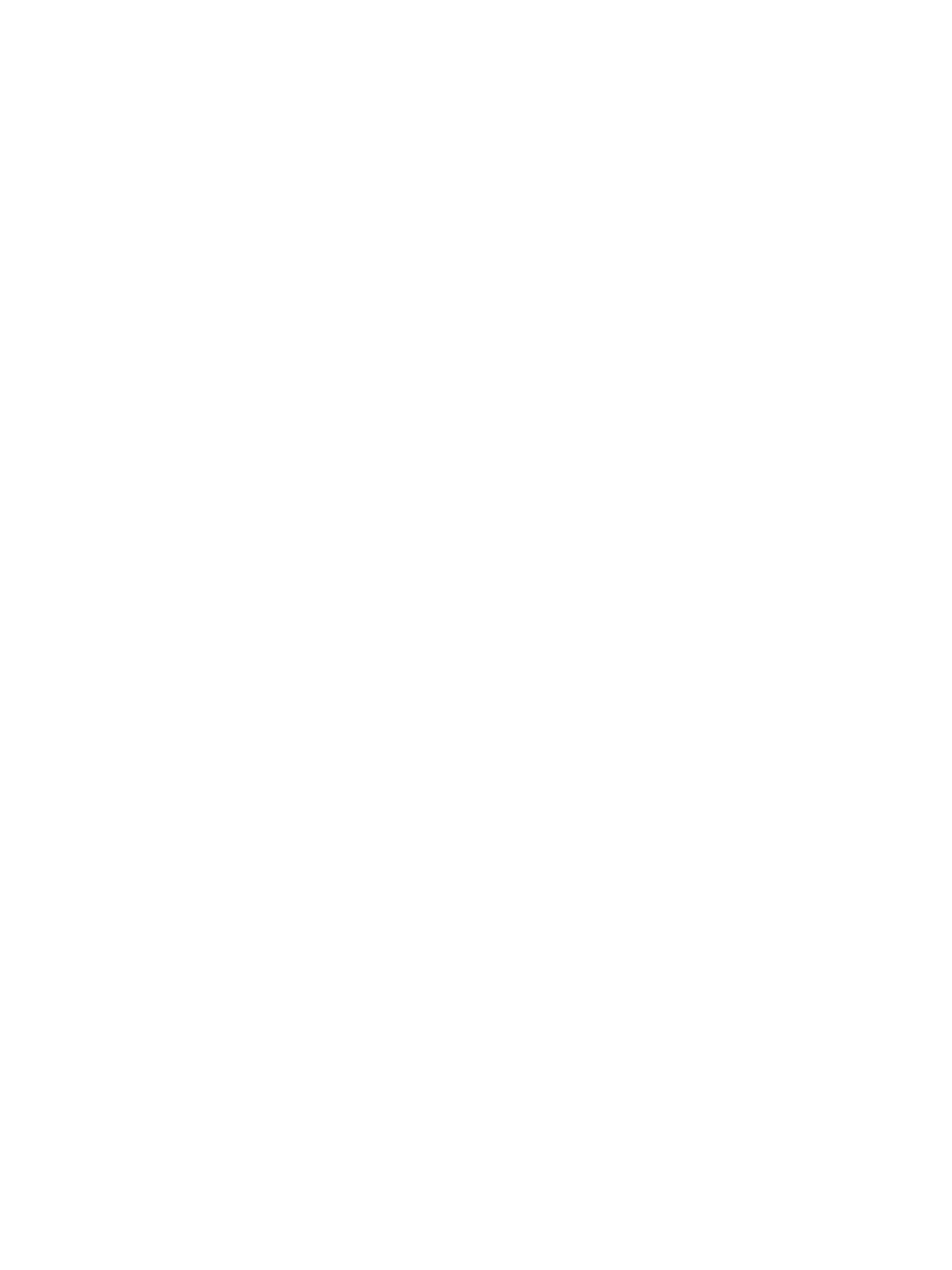

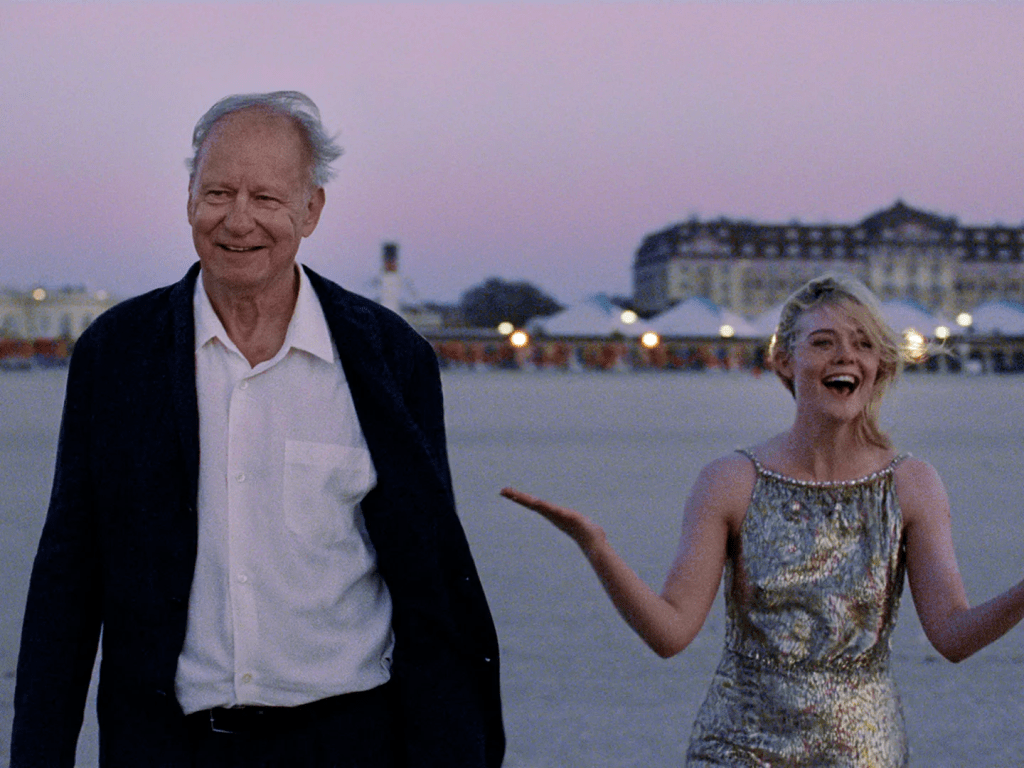

Of course, none of this works without the cast, who play their roles with layer upon layer of emotional nuance. Nora (Renate Reinsve) and Agnes (Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas) are still reeling from the recent death of their mother — an event that brings expected grief and unexpected disruption. Her passing pulls their estranged father, Gustav (Stellan Skarsgård), back into their orbit after years of absence. Suddenly, a reunion neither daughter ever prepared for materializes, dredging up old wounds, dormant frustrations, and the kind of unspoken history that sits heavy in the air before anyone even says a word.

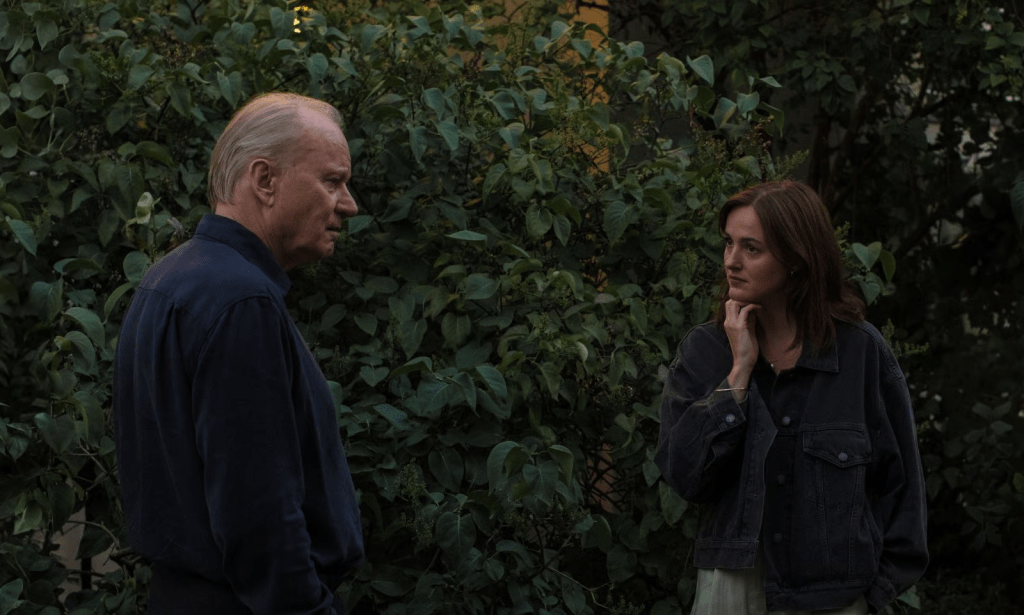

Gustav himself is introduced as a once-respected, now-fading filmmaker trying to claw his way back into artistic relevance. He returns with a passion project — a film deeply personal to him — and immediately tries to recruit Nora as his lead. She refuses, setting into motion a ripple effect of insecurities and lingering resentments. He then chases a bigger name, Hollywood star Rachel Kemp (Elle Fanning), after screening his older work at a festival catches her attention.

This premise fractures the film into a series of narrative shards — scenes, moments, and emotional beats that often end abruptly on a cut to black, almost like chapters in a play. Trier plays directly with the “film within a film” structure, using it not as a gimmick but as a way to illuminate the blurred lines between artistic expression, personal history, and the people we claim to know.

One moment, we’re immersed in Nora’s reality: her work in theater, her dynamic with her troupe, her search for purpose without sacrificing her boundaries. The next, we’re following Gustav and Rachel, sharing unexpectedly tender scenes on the beach, discussing creativity, aging, and the kind of mentorship that blurs into longing. The film jumps seamlessly between these threads, shining a light on every corner of this family — and, importantly, on the house at the center of their lives.

The house is not just a setting; it’s the emotional backbone of the entire story. Trier establishes this immediately, invoking young Nora’s reflection on whether the home feels fuller with people inside — even if those people are fighting — or if it prefers the quiet emptiness that follows departure. The house becomes the physical manifestation of the family’s entire history: a place that has absorbed joy and conflict, tenderness and regret, love and absence. It is both a refuge and a haunting, a vault of memories and the stage on which past damage resurfaces.

Their mother’s death sets everything into motion. Nora and Agnes confront the sudden reappearance of a father who left them when they needed him most. Gustav, meanwhile, is forced to reckon not only with the death of his former partner but with the resurfacing of his own childhood, his strained relationship with his own mother, and the autobiographical ghosts embedded in the screenplay he’s trying to make. Trier places these three under a microscope, not to judge but to study — to reveal the contradictions that make them human. The emotional layering becomes rich, complex, and surprisingly universal, no matter where you stand in your own family story.

Visually, the film is breathtaking in its restraint. Trier and cinematographer Kasper Tuxen transform the house into a living organism. Cracks in the walls, old wooden textures, shifting light — everything feels purposeful. Through their lens, we travel across generations: each family leaving their aesthetic mark on the place, each era carrying its own emotional residue. These transitions build on one another until they converge in the present day, where the weight of history presses against the present narrative of Gustav, Nora, and Agnes. It’s stunning, quiet work — the kind of visual storytelling that sneaks up on you emotionally, then refuses to let go.

There is so much to be said about this film, yet only so much I can reveal without spoiling the quiet shocks and emotional revelations that make Sentimental Value such a rich experience to witness firsthand. I’d love to single out one performance, one craft element, or one narrative thread as the standout, but the truth is that the film works because everyone commits fully. Every actor, every department, every narrative layer feels in sync. It’s a collective effort in the truest sense — and that’s often what makes a film feel whole.

Ultimately, Sentimental Value folds layer upon layer into its exploration of family dynamics, showing how communication — or the inability to muster it — can be the most fragile part of all. Within the confines of this world (which reflects our own with startling accuracy), art becomes the primary language for expressing the feelings these characters struggle to articulate. Gustav channels his grief and unresolved childhood through his new script while trying, however imperfectly, to reach his daughters. Nora, immersed in her theater work, processes her emotions both onstage and off, with the lines between performance and reality constantly blurring. Agnes, the sister who seems the most “stable,” is confronted with her own complicated history with her father’s industry and finds herself researching the past for his new film — a journey that forces her to confront her grandmother’s legacy and the emotional history embedded within the house.

Hollywood loves stories about itself — and in some ways, this film fits neatly into that lineage. But it’s also something more delicate, more introspective. Yes, the narrative circles back to the power of art, but Trier uses the filmmaking motif not as a self-congratulatory flourish, but as an emotional tool. Art becomes therapy, catharsis, confrontation. It becomes the way this family tries to make sense of their grief, their shame, their love, their unfinished business. And that’s where the film truly succeeds: Trier prioritizes the inner lives of the people at its center, not the machinery of filmmaking. The heart comes first. The cinema comes second.

In the end, Sentimental Value isn’t simply a film about filmmaking or family — it’s about the way art and memory intertwine, the way we use stories to explain ourselves to the people we love. It’s a reminder that healing rarely happens cleanly, but it can happen beautifully. And in Trier’s hands, that beauty becomes undeniable.