We are living in a fascinating year filled with new narratives and vivid emotions around parenthood. It has become a phenomenon in its own right. The shifts that are evident are the diverse ways in which this moment is being depicted. Thus far this year we’ve seen a wide and balanced set of stories — and Die My Love from Lynne Ramsay and Frankenstein from Guillermo del Toro expand that palette in oddly parallel ways.

These are two films that essentially start with the same notion at their core — creation, responsibility, transformation — yet unravel in very different styles and from very different vantage-points. In Frankenstein, del Toro places our protagonist, Baron Victor Frankenstein (Oscar Isaac), at the centre of his hubris and intellect, and scrutinises fatherhood and humanity. The question “Who is the real monster?” looms large. The film also gives us Frankenstein’s own point of view. While the film does not shy away from violence, it invites empathy as Frankenstein’s creature begins to learn life and language under the guidance of a blind man. That shift places the creator and the created in a new light — raising questions about a creator’s responsibility to its creation.

On the other side, Ramsay’s Die My Love is not her first film to explore a parent’s dissolution into chaos, but it keeps to her disturbing, uncomfortable aesthetic. Grace (Jennifer Lawrence), a writer, relocates with her partner to rural Montana, becomes pregnant, and struggles with postpartum depression in uncanny, escalating ways. We are reminded again that your creation can exact a cost you never anticipated. In Frankenstein’s case, it is not pregnancy but the fear (or loathing) of death, and the ambition to solve it, that drives Victor Frankenstein. While Grace’s breakdowns feel inevitable within her domestic context, Victor’s creation is born of reckless ambition, not maternal instinct — and the consequences are framed differently.

The result of screening these two films back-to-back is one of rogue parenthood — the term “postpartum” may not strictly apply to Baron Victor, but the same concerns around creation, responsibility, alienation and aftermath resonate. Whether natural or unnatural, the act of making something — a child, a being, a world — carries deep emotional weight. These films display that weight at a visceral level, and they are also visually arresting, rich in imagery and metaphor.

Frankenstein

Release Date: Streaming on Netflix November 7, 2025.

Runtime: 150 minutes (2h 30m)

Rated: R — grisly images, bloody violence

Production Companies: Double Dare You, Demilo Films, Bluegrass 7

Producers: Guillermo del Toro, J. Miles Dale, Scott Stuber

Editing: Evan Schiff

Music / Composer: Alexandre Desplat

Frankenstein (2025)

Director & Screenwriter: Guillermo del Toro

Starring: Oscar Isaac, Jacob Elordi, Mia Goth, Christoph Waltz, Felix Kammerer, Charles Dance

It’s no mystery that Guillermo del Toro’s *Frankenstein (2025) brings fresh ideas and a sharper focus on “the monster” than Mary Shelley’s original novel. Del Toro is now 61, at a seasoned point in his career; Shelley was just 20 when she wrote Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus in 1818 — brilliant for what she achieved, and timeless for having done it. As cinematic interpretations of the tale continue to evolve — most recently seen in the 2023 film Poor Things by Yorgos Lanthimos — Del Toro literally retraces the classic timeline and structure, while flipping narrative details and repeatedly asking: Who is the real monster?

One of Del Toro’s most profound moves in this version is giving the Creature (and in effect, Frankenstein) a deeply emotional point of view. While Shelley originally gave the Creature his own voice, many film adaptations have simplified or omitted that interior life. Del Toro emphasises it. The result is one of the film’s most affecting segments: we witness what Frankenstein endures at the hands of his father, Baron-Leopold Frankenstein, including physical and emotional abuse, and we watch the Creature, still learning how to be in the world, internalize that violence. The question becomes: where does violence sit on the spectrum of nature vs. nurture?

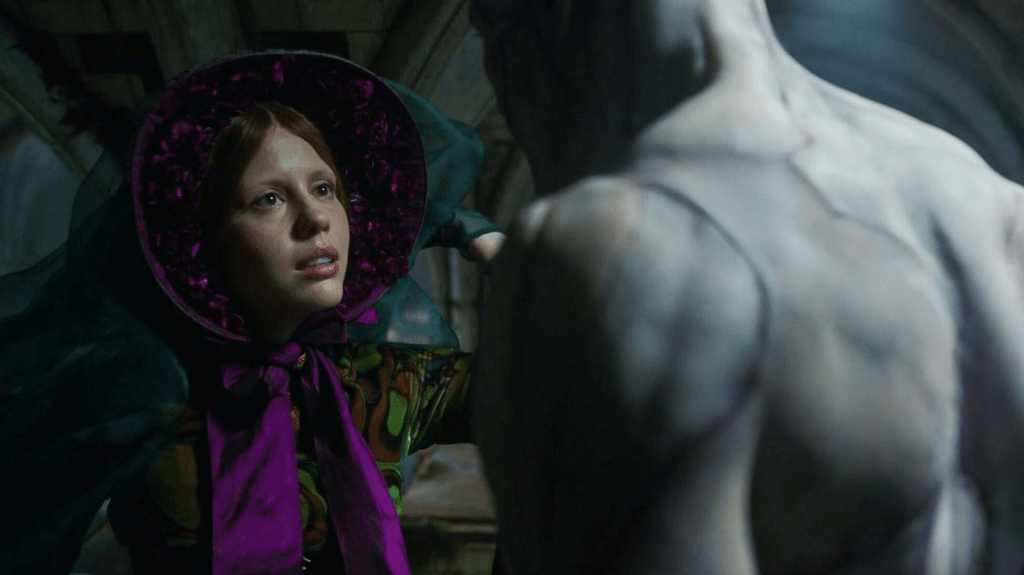

Later, when the Creature finds what seems to be a safe sanctuary — after fleeing a catastrophe that would have destroyed anyone else — we watch a transformation unfold. He is among the very men who once attacked him; he is hidden in their house, learning language and life through the cracks of a wall. Baron Frankenstein’s aggression was direct and deliberate — but the Creature’s gestures of kindness, unseen and unrewarded, become arguably more powerful. It shows how subtle acts of humanity can outweigh even the most flagrant wrongs.

Mary Shelley herself carried a troubled, complicated history with parenthood — including multiple miscarriages and the loss of several children — and these experiences undeniably informed Frankenstein. So while some may complain that del Toro’s adaptation “strays” from the original text, what he actually does is read between the lines, translating Shelley’s metaphors into something more literal, embodied, and emotionally direct. It’s an interpretation that expands the novel’s subtext rather than replaces it — and it does so with striking beauty.

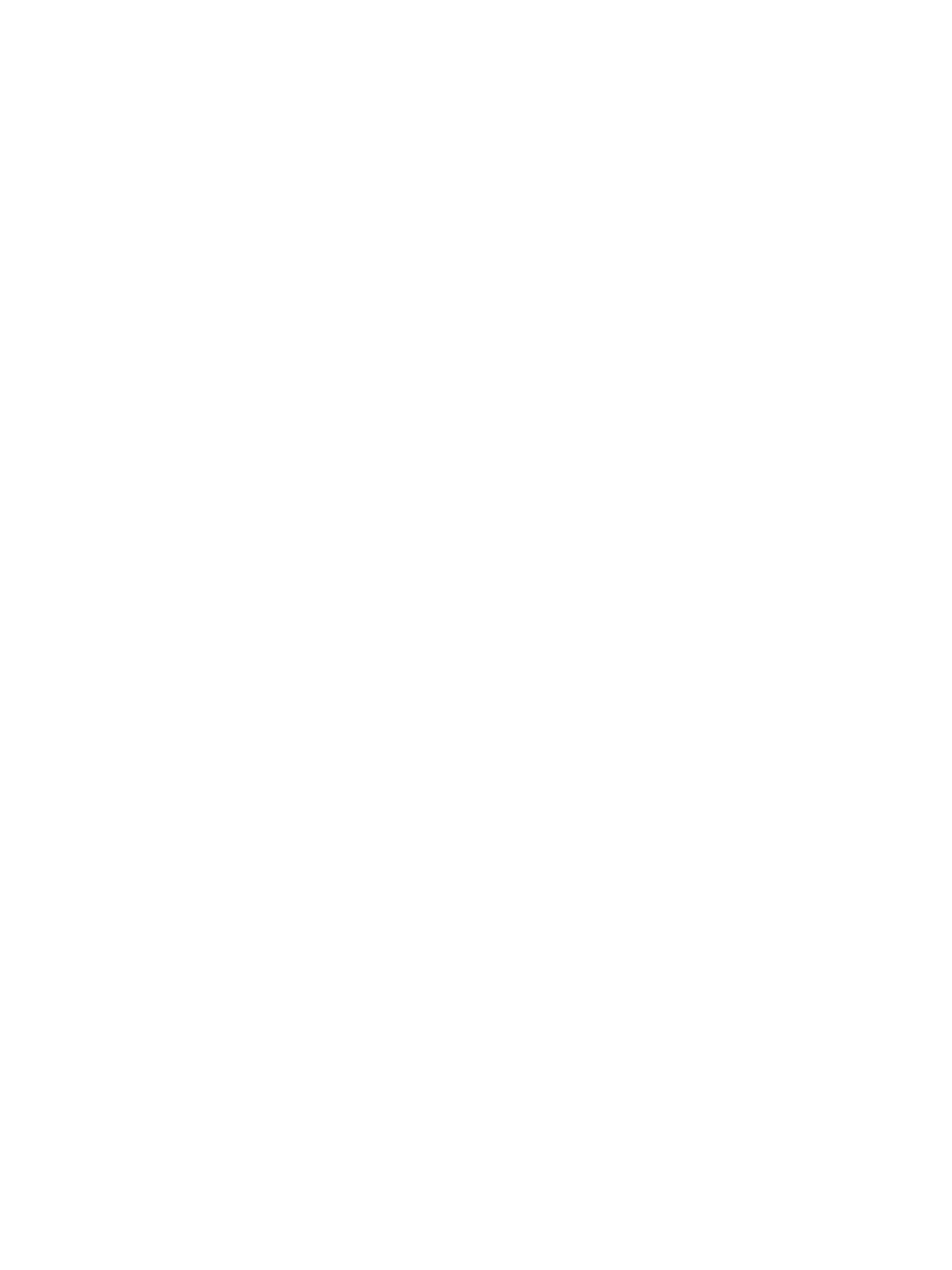

Mia Goth’s Elizabeth adds another charged layer. In this version, she takes on a slightly altered role as the wife of the Baron’s brother, forming a hybrid relationship to the Creature — part maternal, part romantic, part existential mirror. Her presence complicates the Creature’s understanding of affection and belonging, deepening the film’s emotional stakes.

Frankenstein remains a classic because of its timelessness. Even two centuries later, its core resonates — the fears, failures, and psychological ruptures that can emerge after creation, whether literal or metaphorical. Del Toro’s version filters that timelessness through the lens of parenthood: what it means to make life, to reject it, to fear it, to shape it, or to flee from the responsibility it demands.

Del Toro has always been able to merge magic and melancholy, wonder and dread, crafting worlds that feel both enchanted and haunted. Frankenstein is no exception. The film is visually breathtaking — its wide, sweeping shots are almost painterly — yet the beauty of the frame is in constant tension with the internal battles its characters face. The Baron’s obsession with conquering death, the Creature’s search for identity and tenderness, and the surrounding human cowardice and cruelty all collide in a world that is gorgeous on the outside and fractured within. It’s a fitting reflection of creation itself: awe mixed with terror, invention mixed with consequence.

Die My Love

Release Date: November 7, 2025 (USA)

Runtime: 119 minutes (1h 58m)

Rated: R — language, graphic nudity, sexual content, some violent content

Production Companies: Black Label Media, Excellent Cadaver, Sikelia Productions

Producers: Martin Scorsese, Jennifer Lawrence, Justine Ciarrocchi, Molly Smith, Thad Luckinbill, Trent Luckinbill, Andrea Calderwood

Cinematography: Seamus McGarvey

Editing: Toni Froschhammer

Music / Composer: George Vjestica, Raife Burchell, Lynne Ramsay

Die My Love (2025)

Writer: Enda Walsh, Lynne Ramsay, Alice Birch (based on the novel by Ariana Harwicz)

Starring: Jennifer Lawrence, Robert Pattinson, LaKeith Stanfield, Sissy Spacek, Nick Nolte

A more “traditional” yet deeply traumatic take on a postpartum world, Lynne Ramsay offers an unsettling window into her protagonist’s chaotic mind. By “traditional,” I mean she isn’t bringing a creature to life from corpse parts—but the narrative is anything but conventional. Jennifer Lawrence delivers perhaps one of the year’s finest performances, and in a moment saturated with parent-role films (most recently If I Had Legs I’d Kick You from Mary Bronstein), she stands out. While Ramsay’s film and Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein may not align in every aspect, the core essence of each—the burden of creation, isolation, emotional collapse—overlaps, offering distinct perspectives on the same thematic substance.

Grace (Lawrence) and Jackson’s (Robert Pattinson) relationship is a roller-coaster, set off by their newborn (unnamed) baby. Their story is fragmented, non-linear—the structure mirroring Grace’s mental state: chaotic, unraveling, anxious. The film deliberately makes you uncomfortable, impatient, unsettled—channeling the full spectrum of emotions that may arise in the postpartum period, especially depression. Grace has physical outbursts, slips into daydreams, acts impulsively. Yet through all that, she still cares for her child. As manic and dangerous as she can appear, there remains that tether of parental responsibility.

Similar to Frankenstein, Die My Love is rooted in literature—an adaptation of Ariana Harwicz’s fierce, hallucinatory novel—and it, too, dives into the rupture and rawness of postpartum reality. But where Frankenstein externalizes creation through a stitched-together body, Ramsay internalizes it, placing us inside the volatile, unfiltered consciousness of a mother struggling to feel tethered to her own newborn.

Jackson’s decision to uproot their lives and move them to rural Montana becomes the catalyst, along with the birth of their newborn, for Grace’s unraveling. While he disappears into “work”—and from the film’s perspective, possibly into more than that—Grace is left alone in the house, her days collapsing into isolation, sexual frustration, and the vertigo of an identity reshaped by birth. Her loneliness becomes a geography unto itself.

Ramsay’s lens on postpartum despair isn’t surface-level; it’s intimate, unsettling, philosophical. Through Jennifer Lawrence’s electrifying performance, Grace becomes a prism for the contradictions of motherhood. From one newborn life springs a chaotic spectrum of emotion—lust, self-destruction, longing, fury, the desire for escape. Ramsay and Lawrence create something jagged yet strangely beautiful, constantly pushing against the sanitized narratives we tend to impose on new mothers.

The film’s sharpest, most lingering theme is disconnection. Birth is typically framed as miraculous, transcendent, celebratory—but what happens when that connection doesn’t immediately form? What if the bond feels delayed, fractured, or unreachable? Is there guilt in that distance? Shame? Fear? And beneath it all, what kind of loneliness grows from wanting something—affection, autonomy, passion, relief—that motherhood suddenly makes harder to grasp?

Die My Love suggests that these questions aren’t aberrations; they’re part of the psychic terrain of creation itself. And in that sense, Ramsay’s film sits in conversation with Shelley’s: both works grapple with the terrifying, transformative space between creator and creation, and the emotional fallout when that bond refuses to fall neatly into place.

Together, Frankenstein and Die My Love form an unexpected conversation across centuries, genres, and bodies. One is gothic myth reimagined; the other is contemporary domestic horror. Yet both confront the same haunting truth: creation is never neutral. It alters the maker as much as the made. It fractures, reshapes, resurrects.

Del Toro externalizes that transformation through a body pieced together, learning the world with brutal innocence; Ramsay internalizes it through a mind splitting at the seams, caught between desire, despair, and duty. One story watches a creator flee the weight of responsibility, the other watches a creator crushed beneath it. And in both, the aftermath is where the real horror — and the real humanity — resides.

What lingers after pairing these films isn’t just the violence, or the spectacle, or even the discomfort. It’s the recognition that creation, in all its forms, is an act of vulnerability. Of surrender. Of risk. Whether the birth is literal or imagined, whether the outcome is monstrous or miraculous, the emotional terrain remains frighteningly similar.

Two tales. Two creators. Two collapses. And a reminder that becoming responsible for another life — any life — forces us to reckon with the parts of ourselves we would rather not see. These films just have the courage to look.