Death of A Unicorn (2025)

Directed by: Alex Scharfman

Starring: Paul Rudd, Paul Rudd, Will Poulter, Téa Leoni, Richard E. Grant

Unicorns have long been seen as symbols of purity and beauty, but Alex Scharfman flips that mythology on its head, crafting a world where these creatures are anything but majestic. Paul Rudd and Jenna Ortega lead this darkly comedic horror film as father-daughter duo Elliot and Ridley, who, on their way to a corporate retreat hosted by Elliot’s boss, Odell Leopold (Richard E. Grant), accidentally strike a unicorn with their car. What follows is a moral tug-of-war, forcing them to confront the consequences of human intervention in nature—especially when greed, mortality, and power come into play.

Horror has always had the unique ability to explore sensitive topics through its tropes and motifs. Adding comedy to that equation is even trickier, but Death of a Unicorn largely succeeds in balancing the two. The film thrives on its performances, with Rudd and Ortega’s dry humor playing off each other seamlessly. Will Poulter is a standout, fully committing to his role with a natural comedic edge, while Téa Leoni (as Leopold’s wife, Belinda) and Anthony Carrigan (as Griff, the family butler) add unexpected emotional weight. Scharfman makes strong use of his cast, blending their strengths into a well-rounded ensemble.

At its core, the film raises thought-provoking questions about the morality of valuing one species over another. It critiques the unchecked power of the ultra-wealthy—what the 1% can access and, more importantly, how they choose to use it. The film invites introspection: if faced with the same situation, what choices would you make? Themes of exploitation, greed, nature, and mythology weave through the satirical narrative, though the film’s absurdity (and over-the-top gore) may lose some viewers along the way. The swings it takes in storytelling are bold, if occasionally uneven, but they’re undeniably entertaining. Where the dialogue may falter in places, the chaotic action sequences, elaborate gore, and sheer absurdity of the group’s misadventures keep the energy high.

Ultimately, Death of a Unicorn takes the mythical and turns it monstrous, reframing unicorns as creatures that are not only physically overpowering but also spiritually and magically superior. It plays with the irony of their dual nature—both dangerous and miraculous—while weaving in a familiar story of wealth and greed interfering with the natural order. Throw in some CGI fantasy elements, bursts of sharp humor, and a few grotesquely fun surprises, and you get a film that, for better or worse, is one of a kind. In a world full of horses, it at least tries to be a unicorn.

Before scrolling to the next review, please note: The Woman in the Yard contains discussions of suicide and grief. If these topics are difficult for you, please proceed with caution.

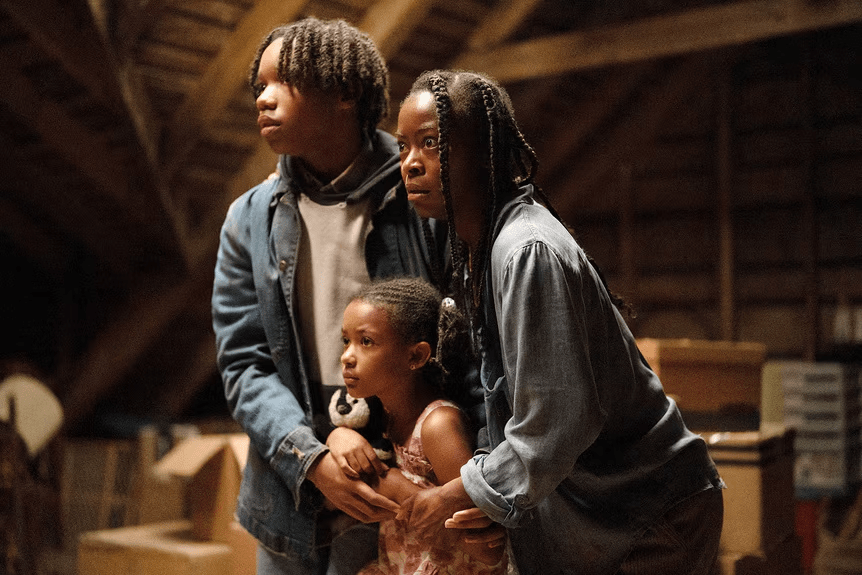

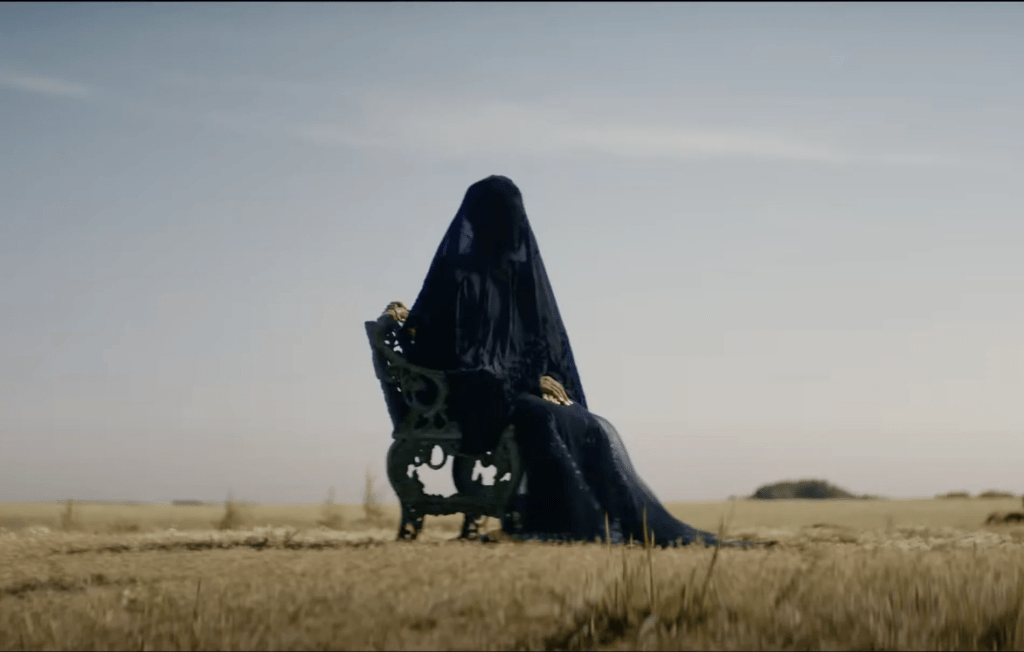

The Woman in the Yard (2025)

Directed by: Jaume Collet-Serra

Starring: Danielle Deadwyler, Peyton Jackson, and Estella Kahiha

Horror has always been a powerful medium for tackling taboo and stigmatized topics—subjects we often avoid at the dinner table. Whether subtle or in-your-face, the genre provides a unique lens for exploring difficult themes. In The Woman in the Yard, Jaume Collet-Serra crafts a narrative around grief, depression, and suicide, using shadow work and strong acting direction to shape an unsettling psychological horror experience.

At its core, the film thrives on Danielle Deadwyler’s gripping performance as Ramona, a grieving mother struggling to care for her two children, Taylor (Peyton Jackson) and Annie (Estella Kahiha), after the tragic loss of her husband. The film’s exploration of mental health is bold, but it also raises the question of how far a story can push these sensitive topics before crossing a line. While Deadwyler’s performance carries much of the emotional weight, the film stumbles in defining its perspective—who are we meant to root for? How does the timeline truly unfold? And does its portrayal of suicidal ideation feel honest or exploitative?

That said, The Woman in the Yard takes creative swings that deserve appreciation. Though it treads familiar thematic ground, it excels in its cinematography, editing, and sound design. The shadow work, while not entirely original, is used beautifully—if eerily—to heighten the film’s atmosphere. The camera work, particularly during chaotic moments, effectively places us in Ramona’s spiraling mental state. The blocking and framing of “The Woman in the Yard” herself create some truly chilling visuals, while diegetic sound and an ominous score amplify the tension and fear felt by Ramona and her children.

Where the film falters is in its narrative cohesion. The pacing is steady, but character motivations become murky. What does Ramona ultimately want? Are we meant to sympathize with her or question her reliability? And how should the children realistically react to their mother’s unraveling psyche? The ambiguous ending invites interpretation, but it may leave audiences questioning whether the film handles its heavy themes responsibly.

Despite its narrative shortcomings, The Woman in the Yard remains an engaging watch, bolstered by Deadwyler’s performance, eerie imagery, and superb sound design. Collet-Serra paints a dark, grim world, immersing us in Ramona’s fractured reality. Whether it leaves you unsettled or unsatisfied, the film undeniably sparks discussion—something horror does best.